Governments of the Amazon are reaffirming their goals of pursuing green investment – all while expanding fossil fuel exploration and mining

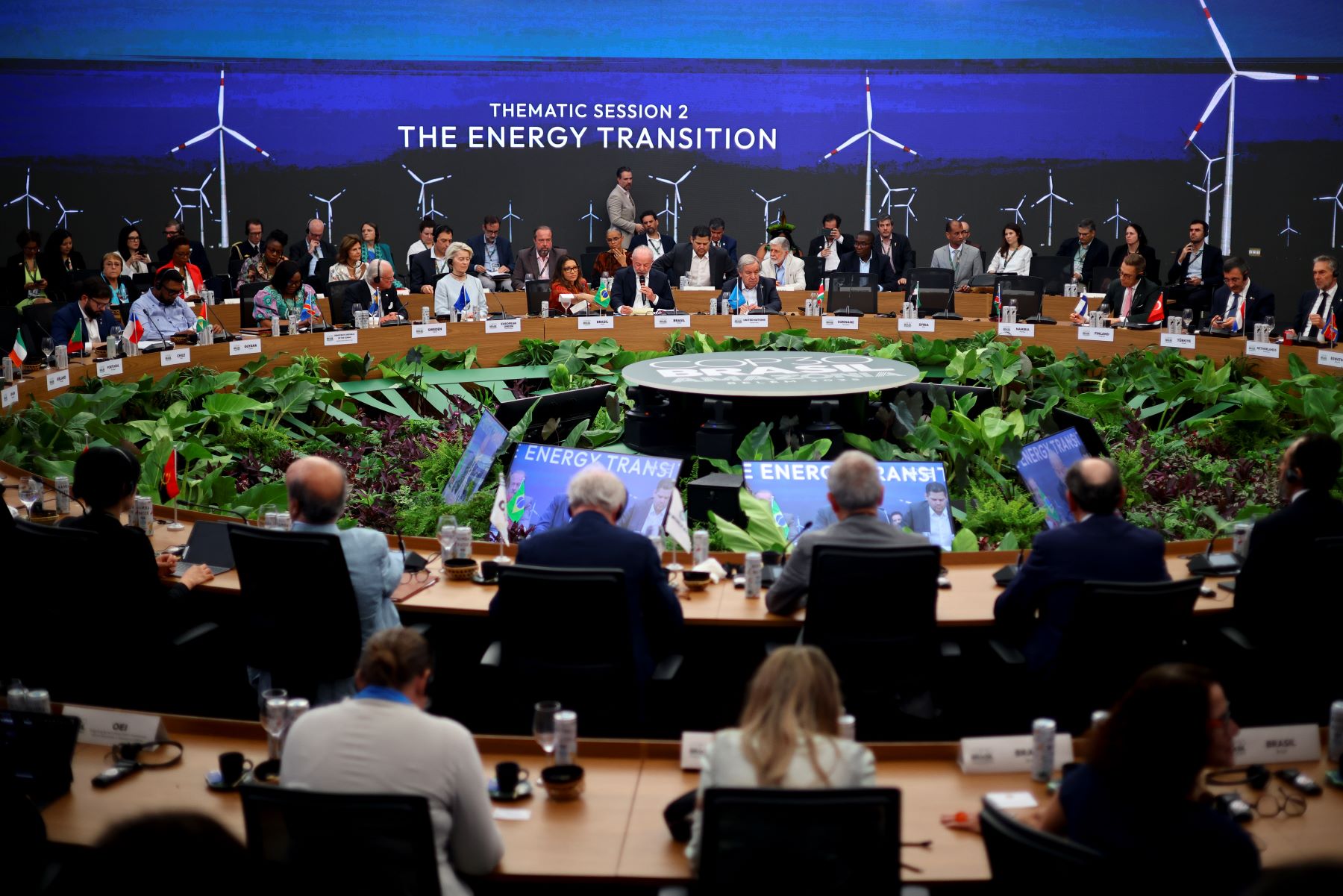

In November, the world will turn its attention to the Brazilian city of Belém, as it hosts the COP30 summit. In its thirtieth edition, the UN’s annual climate conference, which aims to accelerate international efforts to mitigate and adapt to climate change, will for the first time take place in the Amazon, one of the most vital biomes for Earth’s climate balance.

But while the forests of the Amazon are fundamental to global climate regulation, they face growing pressure from extractive industries – especially fossil fuels. As COP30 approaches, this tug-of-war between preservation and exploitation is becoming increasingly clear.

“The Amazon is a geopolitical asset for the region,” says Joubert Marques, climate and geosciences analyst at the Arayara International Institute, an organisation monitoring oil, gas and mining projects in the Amazon. “When it is strategic – especially in the search for financing – governments adopt a pro-conservation discourse. But this discourse seems to disappear when it comes to oil and gas.”

Host nation Brazil epitomises this paradox.

President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva has consistently reiterated the government’s intention to explore for oil in the waters of the country’s so-called “equatorial margin”. This new frontier includes the offshore Foz do Amazonas basin, a sensitive area where the Amazon River meets the sea, which harbours little-explored coastal ecosystems – not to mention the immense biodiversity of the land adjacent to the shore. On 20 October, amid intense political pressure, Brazil’s environmental agency Ibama granted a licence for state oil firm Petrobras to begin the exploratory drilling in this contentious area, which should start “immediately,” according to the company.

A month before the start of COP30, Brazil’s fuel exploration regulator, the National Petroleum Agency (ANP), had also announced the inclusion of 275 new oil and gas blocks in an auction scheduled for 2026. The decision brought the total number of areas under permanent offer since June to 451. According to the Arayara Institute, some of these overlap with Indigenous territories and conservation units.

At the same time, Brazil’s delegation will showcase two ambitious measures at the Belém conference: the Open Coalition for Carbon Market Integration and the Tropical Forests Forever Fund (TFFF). Both are designed to establish the value of standing forest, thus turning conservation into an income opportunity.

The coalition’s proposal takes into account that more than 70% of Brazil’s carbon credit projects are in the Amazon. The revenue from their sale could potentially reach USD 21.6 billion by 2030. The TFFF – the Brazilian government’s pride and joy for COP30 – proposes an enhanced model of financing for forests which, instead of only rewarding countries for reductions in deforestation, provides payments for the ongoing preservation of forested areas. At the United Nations General Assembly in September, the Brazilian government announced a contribution of USD 1 billion to the fund. A total of USD 125 billion is expected from other sources.

Repeated promises, timid action

This gap between rhetoric and practice is not unique to Brazil. Across the region, Amazonian governments have reaffirmed environmental commitments and sought green investments, while cooperation and concrete, enduring results on preservation remain limited.

In August, the Summit of Presidents of the Amazon Cooperation Treaty in Bogotá, Colombia, brought together its eight member countries to reinforce a common protection agenda for the biome. The resulting Bogotá Declaration features commitments on technical cooperation, combating environmental crimes and strengthening the presence of the state (especially in border areas), as well as actions to halt and reverse deforestation.

The declaration represented the “reactivation of an important diplomatic process that could lead to common agreements for preservation,” according to Ilan Zugman, who directs the Latin America and Caribbean region at 350.org, an NGO working to end fossil fuel dependence.

Still, according to observers and organisations that followed the summit, the declaration has significant omissions. Those observers interviewed by Dialogue Earth consider the text a missed opportunity to recognise oil and gas exploration as one of the main threats to the Amazon. The lack of concrete targets, including on ending deforestation, also caused frustration among participants. If the Bogotá Declaration serves as a barometer for COP30, the sensitive issue of fossil fuels could be left out of the discussions.

“The generic language of the declaration is clear evidence of the region’s difficulty in reconciling rhetoric with practice, especially in the debate on fossil fuels,” says Karla Maass, advocacy advisor for the Climate Action Network Latin America.

During the summit, Lula defended the Amazon as a unified region, and multilateralism as the way to tackle the climate crisis. For Maass, the recognition of this unity – albeit largely rhetorical – is a particular geopolitical feature of the biome. She notes, however, that this view is rarely reflected in multilateral forums, such as the COPs, where issues such as fossil fuel exploitation often divide the region’s governments and lead them to different negotiating blocs.

“As different perceptions of the Amazon coexist in the region, national proposals do not always converge,” says Maass. “Even when the forest is used as a bargaining chip in negotiations, each country uses it in its own way.”

Internal divisions intensify

On the eve of COP30, pressure is also growing from some parliamentarians in Amazonian countries to end fossil fuels. On 8 October, representatives from six South American nations delivered a report to the Brazilian government on the “profound” damage caused by five decades of industry in the Amazon. Meanwhile, nearly 800 legislators have signed an open letter calling for a fossil fuel-free future for the region.

Among the proposals, presented by the multinational coalition Parliamentarians for a Fossil Fuel-Free Future, is the creation of a joint moratorium on the expansion of mining and fossil fuel extraction throughout the Amazon biome. The measure has regional support, but so far only five countries – Bolivia, Colombia, Peru, Ecuador and Brazil – have presented bills on the subject in their respective parliaments.

In Colombia, President Gustavo Petro vetoed the signing of new oil and gas exploration contracts in 2023, maintaining only those contracts already in force. The decision marked a turning point in the country’s energy policy, but the future is uncertain: Petro cannot run for re-election in 2026, as per the constitution, and Colombia’s fragmented political landscape could unravel his legacy.

Juan Carlos Lozada, a Colombian MP and member of Parliamentarians for a Fossil Fuel-Free Future, tells Dialogue Earth that while Petro’s policies already function, in practice, as a moratorium, “legal mechanisms to make them sustainable in the long term” are needed. Despite political resistance, Lozada believes Colombia can move forward with this agenda: “In Colombia, we could reach an agreement to ban future exploration, at least in the Amazon.”

Meanwhile, exploration continues to gain momentum: between 2022 and 2024, the region accounted for about 20% of oil reserve discoveries worldwide. This has consolidated its position as one of the primary frontiers for expansion. As a result, Amazonian governments continue to promote these sectors.

In August, President Lula partially vetoed a legal proposal dubbed the “Devastation Bill” by its opponents, blocking some of its most controversial provisions. The rest of the bill is now law and has loosened Brazil’s environmental licensing requirements; a key clause that accelerates the approval of projects considered to be strategic – even those with large environmental impacts – remains in place. According to the Arayara Institute, more than 2,600 fossil fuel projects could benefit from the law.

To the north, Guyana – a country where large areas of territory lie within the Amazon – discovered massive oil reserves in 2015. Though almost all of its production is now found offshore, the country is transforming into a global oil power, with exploration has been advancing at a rapid pace.

Guyana’s president, Irfaan Ali, has repeatedly said oil is essential for national development and for financing the energy transition. He promised to continue expanding production and exploration upon his re-election in September.

Maass notes that in Amazonian countries, the prevailing narrative is “that extractive exploitation of the forest is necessary, even to get the resources needed to keep the forest standing.” She says the region has historically been treated as a supplier of raw materials and “governments still cannot see a way out of their dependence on natural resources.”

From extraction to investment

The pressure on the Amazon goes far beyond fossil fuels. Activities such as mining, agriculture and livestock farming have also spread. According to the land monitoring initiative Mapbiomas, more than 88 million hectares of Amazonian forest were destroyed between 1985 and 2023.

Economic expansion in the Amazon has been accompanied by an escalation of illegal activities that take advantage of gaps in law enforcement and the absence of the state. In border areas, deforestation, mining and drug trafficking are intertwined in networks that move billions of Brazilian reais’ worth of goods and money, increasing pressure on communities and preserved forests. “Often, countries do not have sufficient budget and resources to combat these groups,” says Zugman.

It is in this context that cooperation initiatives such as the TFFF gain relevance. But while the fund has been presented as an opportunity to align economic and environmental interests among Amazonian countries, experts warn its effectiveness will depend on the commitment of governments. As Zugman says: “If countries want to use the forest as a bargaining chip – in a good way, to reach more ambitious agreements – they also need to invest more in its conservation. It is not enough to just put the Amazon on display.”

Observers also warn that, to avoid following previous promises that never got off the ground, the TFFF will need to combine transparency and participation by local populations to have a real impact.

Dialogue Earth spoke to Toya Manchineri, general coordinator of the Coordination of Indigenous Organisations of the Brazilian Amazon (COIAB): “We want to better understand how the TFFF will work, and have the guarantee that the resources will go directly to our organisations, which work to provide an environmental service that benefits the entire planet.

“We know that our way of life is crucial to mitigating the effects of climate change – and we need the world to see the Amazon beyond its economic value.”

Fonte: Dialogue Earth

Foto: Reprodução / Agência Brasil